3D Model Compression 2: Introduction to rANS

2025-11-21

Hi, I am Yadokoro from Eukarya.

This is the second in the series of articles on 3D graphics compression techniques, and it will be about the ranged Asymmetric Numerical System.

The ranged Asymmetric Numerical System, or rANS, is a type of entropy codec — a compression algorithm that compresses strings using the probability distribution of their symbols.

Compared to other entropy codecs, rANS is known for its speed and compression ratio: it matches the speed of Huffman coding while providing guaranteed optimality for a given probability distribution.

Polish computer scientist J. Duda introduced the algorithm in 2013 as part of a series of papers on a new family of entropy codecs called asymmetric numerical systems.

The rANS codec quickly became one of the most widely used compression algorithms due to its mathematically guaranteed optimality in compression ratio and computational efficiency.

In fact, it's used by

- Draco (3D mesh codec by Google)

- JPEG XL, AV1 (image/video codec)

- Opus (audio codec)

- Zstd and LZFSE (general compression algorithms by Meta and Apple, respectively)

…to name a few.

It is also known to be embedded in fundamental systems like operating systems and browsers. Yes, rANS is much more widely used than you might think — even now, as you read this article, an rANS coder is likely at work behind the screen of your device!

Although rANS is a general compression technique rather than a 3D model compression technique, we're including it in our journey through 3D model compression algorithms because these algorithms often make heavy use of rANS codecs.

For example, in the first article of the series, we looked at the Edgebreaker algorithm — an algorithm that converts mesh connectivity into a string of symbols. Since rANS can compress strings, we can feed the resulting string to an rANS coder to achieve a better compression ratio.

Moreover, rANS can also compress attribute values such as vertex coordinates and texture coordinates.

In this article, we will cover the fundamentals of the rANS algorithm.

💡 At Eukarya, we're developing draco-oxide, a Rust rewrite of Google's Draco 3D model compression library. Check it out if you're interested!

The rANS Algorithm

Settings and Notations

Suppose for a finite set of alphabets. We fix a strict ordering of .

We may know the probability distribution of these alphabets so that .

Now for a fixed positive integer , we come up with the discretized probability distribution in the sense that and for each .

Furthermore, let . We call the offset to the range of .

Encoding

Now we present the encoding formula. Suppose we want to encode a sequence of symbols from , where is the sequence length.

We set the initial state . Then rANS recursively computes the state values , and the final integer will be our encoded data.

Here's how each recursive step works: Let denote the function representing the encoding step, so that the encoding step can be written as for each time step .

We occasionally write when is fixed.

First, compute the quotient and remainder from the Euclidean division of by . That is, find positive integers and such that

Then is computed by the formula:

The value represents a compressed version of the previous state .

When integers are represented in the -ary (or -decimal) number system, multiplying by shifts each digit one place to the left and inserts a zero in the least significant position, thereby creating space to encode another integer from the set — this is where the range information is encoded.

We first encode the offset to specify which range we're using, then encode the value , which is guaranteed to lie within the range since .

The total range information is also bounded above by due to the design of the ranges.

Decoding

Now we give the formula for the decompression algorithm. Decoding a rANS-encoded data involves reversing the encoding process, that is, the symbol that is encoded at last will be decoded first.

Given the state value after encoding symbols, we need to recover and then compute .

Similarly to the case of encoding, we denote by the decoding function, i.e., for each time step .

We will first compute the Euclidean division of by , that is, we compute positive integers and such that

Since is a positive integer less than , there must be a unique symbol whose range contains , that is,

This can be efficiently implemented using a lookup table that maps each value in to a symbol whose range contains it.

Once we have identified , we can compute by reversing the encoding operation. Note that we have the equations

where and are the values defined in the encoding function in the previous section.

Rewriting the variables and from equation (1) using equations (3) and (4) gives the final decoding formula:

The decoding process continues recursively until all symbols until we hit .

Note that decoding proceeds in reverse order compared to encoding. If we encoded in this order, then the symbols are decoded in the order .

Example

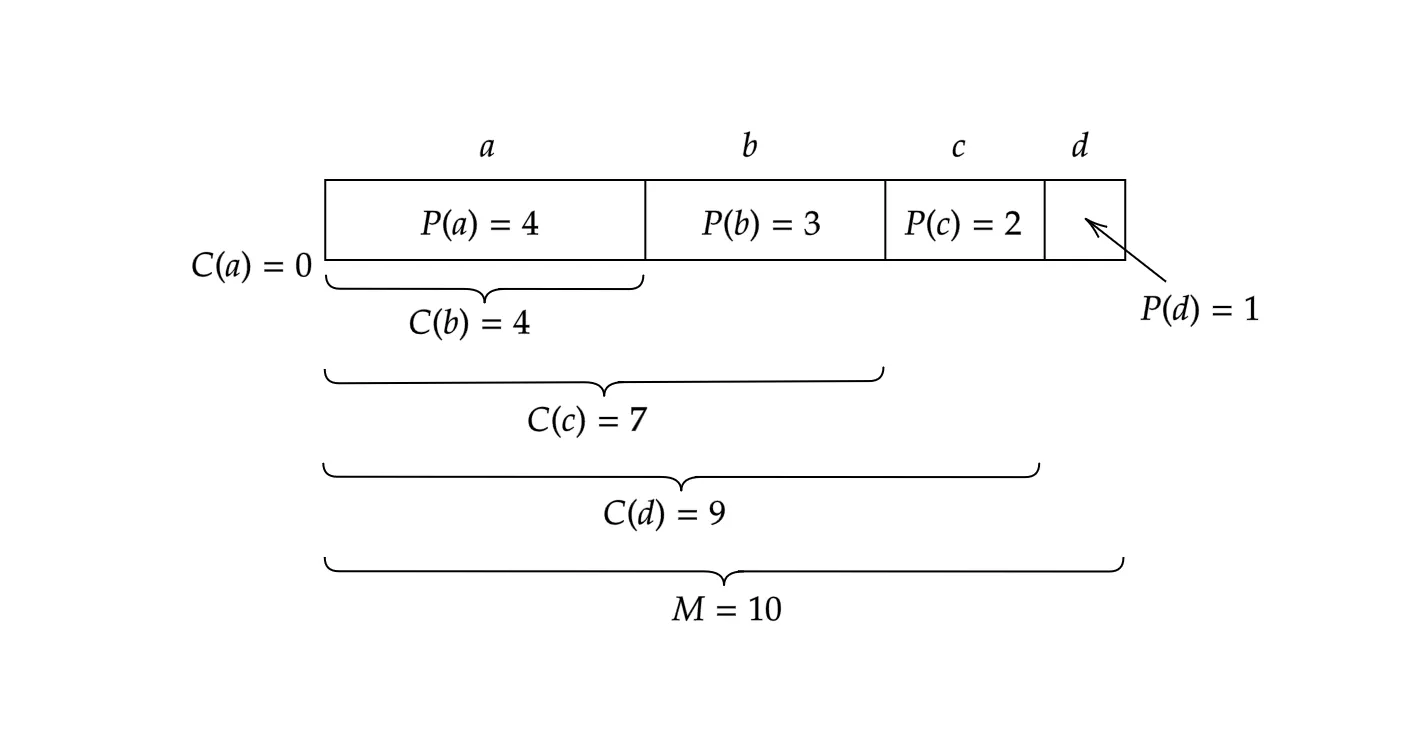

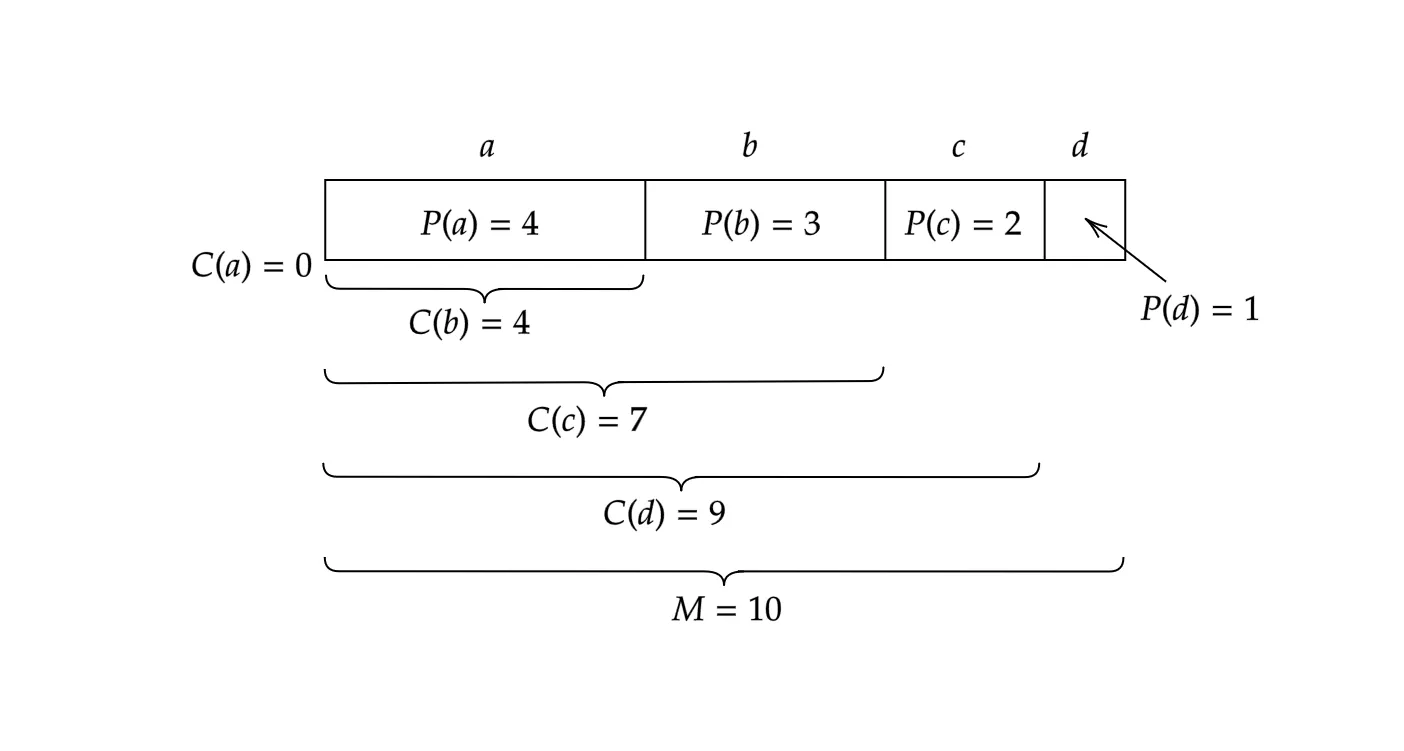

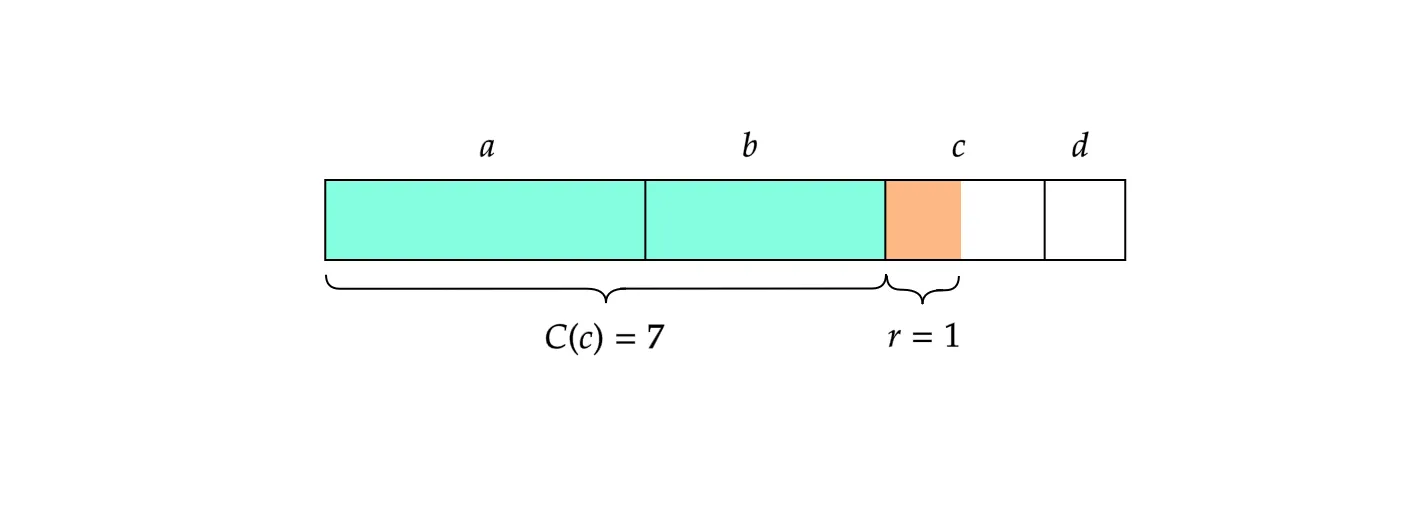

Let’s do a quick example. Suppose that we have the setting of Figure 1 and that we have encoded up to .

Our job now is to encode the 6th symbol, say, “c”. Following the arithmetic, we see that , , , so we obtain .

Fine, but how can we decode the state and the symbol “c” back from ?

Since is less than , dividing by will give the quotient and the remainder .

To decode the symbol and the remainder from , see Figure 2. Because (concretely, ), we know that lies in the range of the symbol “”. Also, we see that has value in the range of “c”, so we figure out .

Thus we obtain .

The Streaming rANS Algorithm

The previous section introduced the rANS codec, whose main idea is to create a single large integer containing all information about the string.

While the rANS coder achieves optimal entropy coding for a given probability distribution, it quickly becomes impractical as string size increases — we must perform Euclidean division on increasingly large integers, which is computationally expensive.

To resolve this issue, we decompose each resulting integer to keep it reasonably small.

This is accomplished by the streaming variant of the algorithm, called the streaming rANS algorithm, which we introduce in this section.

Here's how the streaming rANS coder works:

Streaming Encoding

We choose positive integers and .

The number indicates how many bits each transfer sends in the stream — set this to for the simplest implementation, or to for a byte-stream.

The number is an algorithm parameter; a higher value of makes the algorithm slower but improves compression efficiency.

In this section, we will present a streaming variant where, at each time step, the state value lies between and , i.e., we make sure that with:

To keep the state value inside at each time step, we simply divide the state value by whenever would go out of range .

Ok, but how can we know when the state value is about to overflow? Said another way, what state value and a symbol will be such that ?

To answer this question, we need to know what the set defined by

looks like.

One fact useful to compute this set is that the function is monotonically increasing, that is, as the input gets bigger and bigger, so does the output.

Indeed, the two numbers and with and are all we need to know, as the monotonicity will tell us that any number with will be in as well.

So what are the values of and ? This is in fact a great exercise; if you have extra time, I recommend you close the article now and try to find the answers by yourself.

…welcome back! We should have now arrived at

This clean formula for is in fact thanks to the design of ! Thus we now know that if the state value is inside when trying to encode , then the resulting state value would never overflow.

We are finally ready to explain the algorithm. Given the state , a symbol can be encoded by

One question that remains is: how can we be sure that the while loop terminates in a finite step? Isn’t there a case that division by overshoots the ?

Well, the division by indeed never overshoots the interval , thanks to the design of .

If there is a state value that overshoots the interval , then there must be an integer with .

This means that and , or that and , but either case can never happen.

Streaming Decoding

For decoding, we perform the reverse operations. We start with the last encoded state .

At each time step , we start by decoding a symbol and from using the standard rANS decoding process explained in the previous section.

After decoding a symbol, if the state falls below the lower bound of , we need to read in additional -bits from the encoded bitstream:

You may be wondering whether the number of -bit transfers made during encoding might differ from that during decoding, causing the decoding to fail.

That is, we stop reading the -bit transfers once , but isn’t it too early? — isn’t it possible that as well?

Well, once again, the design of guarantees that there is no integer such that both and are in .

This in turn guarantees that the number of transfers is uniquely determined, so the algorithm does not encounter the ambiguous situation described above.

That is all! We now have a practical rANS algorithm.

Introduction to tANS Algorithm

In this section, we will take a peek at another variant from the ANS family that is closely related to rANS.

In the previous section, we saw the streaming variant of the rANS coder, which limits the state value to a certain range at each time step .

Since is a one-to-one mapping, it means only a finite number of inputs are fed to throughout the entire rANS encoding process.

More specifically, in the streaming variant of rANS, it is sufficient to define for and — there are only finitely many such pairs .

The tANS algorithm (short for tabled Asymmetric Numerical System) is yet another variant of the ANS algorithm that improves speed by creating a table of at the beginning of the encoding/decoding process.

The table reduces the computations of , which include Euclidean divisions and integer multiplications, to a single table lookup.

The challenge lies in the table creation step. We could compute all values of , but this would defeat the purpose of tANS, which aims to avoid these computations.

Jarek Duda's paper [1] presents a method for creating a table for without explicitly computing it, but it is way beyond the scope of this article, so let us stop here for this article.

Conclusion

In this article, we've explored the rANS (ranged Asymmetric Numerical System) algorithm and its streaming variant, which serve as powerful tools for data compression in 3D graphics applications.

We've covered both the theoretical foundations and practical implementations of these algorithms.

The basic rANS coder provides optimal entropy coding based on symbol probabilities, but it faces practical limitations due to the growing size of the state value.

The streaming rANS algorithm elegantly solves this problem by introducing a mechanism to bound the state value, making it computationally efficient while preserving compression effectiveness.

We've also briefly touched on tANS (table-based ANS), another variant of the ANS family that offers different trade-offs between compression ratio and computational complexity.

These entropy coding techniques are crucial in modern 3D model compression pipelines. When combined with other techniques like quantization, prediction, and transform coding, they enable significant reductions in file size while maintaining visual quality.

References

- Duda, J. (2013). Asymmetric numeral systems: entropy coding combining speed of Huffman coding with compression rate of arithmetic coding. arXiv preprint arXiv:1311.2540. https://arxiv.org/pdf/1311.2540

Eukaryaでは様々な職種で採用を行っています!OSSにコントリビュートしていただける皆様からの応募をお待ちしております!

Eukarya is hiring for various positions! We are looking forward to your application from everyone who can contribute to OSS!

Eukaryaは、Re:Earthと呼ばれるWebGISのSaaSの開発運営・研究開発を行っています。Web上で3Dを含むGIS(地図アプリの公開、データ管理、データ変換等)に関するあらゆる業務を完結できることを目指しています。ソースコードはほとんどOSSとしてGitHubで公開されています。

➔ Re:Earth / ➔ Eukarya / ➔ note / ➔ GitHub

Eukarya is developing and operating a WebGIS SaaS called Re:Earth. We aim to complete all GIS-related tasks including 3D (such as publishing map applications, data management, and data conversion) on the web. Most of the source code is published on GitHub as OSS.